AI class unit 7: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 202: | Line 202: | ||

Propositional logic. It's a powerful language for what it does. And there are very efficient inference mechanisms for determining validity and satisfiability, although we haven't discussed them. But propositional logic has a few limitations. First, it can only handle true and false values. No capability to handle uncertainty like we did in probability theory. And second, we can only talk about events that are true or false in the world. We can't talk about objects that have properties, such as size, weight, colour, and so on. Nor can we talk about the relations between objects. And third, there are no shortcuts to succinctly talk about a lot of different things happening. Say if we had a vacuum world with a thousand locations, and we wanted to say that every location is free of dirt. We would need a conjunction of a thousand propositions. There's no way to have a single sentence saying that all the locations are clean all at once. So, we will next cover first-order logic which addresses these two limitations. | Propositional logic. It's a powerful language for what it does. And there are very efficient inference mechanisms for determining validity and satisfiability, although we haven't discussed them. But propositional logic has a few limitations. First, it can only handle true and false values. No capability to handle uncertainty like we did in probability theory. And second, we can only talk about events that are true or false in the world. We can't talk about objects that have properties, such as size, weight, colour, and so on. Nor can we talk about the relations between objects. And third, there are no shortcuts to succinctly talk about a lot of different things happening. Say if we had a vacuum world with a thousand locations, and we wanted to say that every location is free of dirt. We would need a conjunction of a thousand propositions. There's no way to have a single sentence saying that all the locations are clean all at once. So, we will next cover first-order logic which addresses these two limitations. | ||

== First Order Logic == | |||

{{#ev:youtubehd|hFzVZzMPy8Q}} | |||

I'm going to talk about first order logic and its relation to the other logics we've seen so far -- namely, propositional logic and probability theory. And we're going to talk about them in terms of what they say about the world, which we call the ontological commitment of these logics, and what types of beliefs agents can have using these logics, which we call the epistemological commitments. | |||

So in first order logic we have relations about things in the world, objects, and functions on those objects. And what we can believe about those relations is that they're true or false or unknown. So this is an extension of propositional logic in which all we had was facts about the world and we could believe that those facts were true or false or unknown. | |||

Now in probability theory we had the same types of facts as in propositional logic -- the symbols, or variables -- but the beliefs could be a real number in the range 0 to 1. So logics vary both in what you can say about the world and what you can believe about what's been said about the world. | |||

Another way to look at the representation is to break the world up into representations that are atomic, meaning that a representation of the state is just an individual state with no pieces inside of it. And that's what we used for search and problem solving. We had a state, like state A, and then we transitioned to another state, like state B, and all we could say about those states was are they identical to each other or not and maybe is one of them a goal state or not. But there wasn't any internal structure to those states. | |||

Now, in propositional logic, as well as in probability theory, we break up the world into a set of facts that are true or false, so we call this a factored representation -- that is, the representation of an individual state of the world is factored into several variables -- the B and E and E and M and J, for example -- and those could be Boolean variables or in some types of representations -- not in propositional logic -- they can be other types of variables besides Boolean. Then the third type -- the most complex type of representation -- we call structured. And in a structured representation, an individual state is not just a set of values for variables, | |||

Revision as of 06:19, 5 November 2011

These are my notes for unit 7 of the AI class.

Representation with Logic

Introduction

{{#ev:youtubehd|pszEzBql4bw}}

Welcome back. So far we've talked about AI as managing complexity and uncertainty. We've seen how search can discover sequences of actions to solve problems. We've seen how probability theory can represent and reason with uncertainty. And we've seen how machine learning can be used to learn and improve.

AI is a big and dynamic field because we're pushing against complexity in at least three directions. First, in terms of agent design, we start with a simple reflex-based agent and move into goal-based and utility-based agents. Secondly, in terms of the complexity of the environment, we start with simple environments and then start looking at partial observability, at stochastic actions, at multiple agents, and so on. And finally, in terms of representation, the agent's model of the the world becomes increasingly complex.

In this unit we'll concentrate on that third aspect of representation, showing how the tools of logic can be used by an agent to better model the world.

Propositional Logic

{{#ev:youtubehd|_VjyktjNMoM}}

The first logic we will consider is called propositional logic. Let's jump right into an example, recasting the alarm problem in propositional logic. We have propositional symbols B, E, A, M and J corresponding to the events of a burglary occurring, of the earthquake occurring, of the alarm going off, of Mary calling, and of John calling. And just as in the probabilistic models, these can be either true or false, but unlike in probability, our degree of belief in propositional logic is not a number. Rather, our belief is that each of these is either true, false, or unknown. Now, we can make logical sentences using these symbols and also using the logical constants true and false by combining them together using logical operators. For example, we can say that the alarm is true whenever the earthquake or burglary is true with this sentence:

So that says whenever the earthquake or the burglary is true, then the alarm will be true. We use this V symbol to mean "or" and a right arrow to mean "implies".

We could also say that it would be true that both John and Mary call when the alarm is true. We write that as:

And we use this symbol to indicate an "and". So this upward-facing wedge looks kind of like an "A" with the crossbar missing, and so you can remember "A" is for "and" where this downward-facing V symbol is the opposite of "and", so that's the symbol for "or".

Now, there's two more connectors we haven't seen yet. There's a double arrow for equivalent, also known as a biconditional, and a not sign for negation. So we could say if we wanted to that John calls if and only if Mary calls. We would write that as:

John is equivalent to Mary -- when on is true, the other is true; when one is false, the other is false. Or we could say that when John calls, Mary doesn't, and vice versa. We could write that as:

And this is the "not" sign.

Now, how do we know what the sentences mean? A propositional logic sentence is either true or false with respect to a model of the world. Now a model is just a set of true/false values for all the propositional symbols, so a model might be the set B is true, E is false, and so on. We can define the truth value of the sentence in terms of the truth of the the symbols with respect to the models using truth tables.

Truth Tables

{{#ev:youtubehd|eOp4UJl0ZIA}}

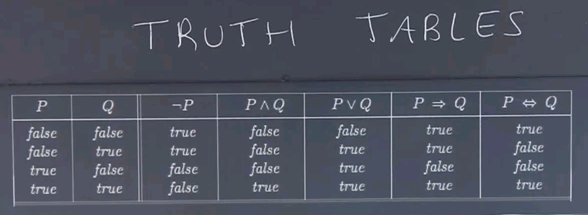

Here are the truth tables for all the logical connectives.

What a truth table does is list all the possibilities for the propositional symbols, so P and Q can be false and false, false and true, true and false, or true and true. Those are the only four possibilities, and then for each of those possibilities, the truth table lists the truth value of the compound sentence. So the sentence not P is true when P is false and false when P is true. The sentence P and Q is true only when both P and Q are true and false otherwise. The sentence P or Q is true when P or Q is true and false when both are false.

Now, so far, those mostly correspond to the English meaning of those sentences, with one exception, which is that in English, the word "or" is somewhat ambiguous between the inclusive and exclusive or, and this "or" means either or both.

We translate this mark into English P implies Q; or as: if P, then Q; but the meaning in logic is not quite the same as the meaning in ordinary English. The meaning in logic is defined explicitly by this truth table and by nothing else, but let's look at some examples in ordinary English.

If we have the proposition O and have that mean five is an odd number and P meaning Paris is the capital for France, then under the ordinary model of the truth in the real world, what could we say about the sentence ? That is, five is an odd number implies Paris is the capital of France. Would that be true or false? And let's look at one more example? If E is the proposition that five is an even number and M is the proposition that Moscow is the capital of France, what about ? Five is an even number implies Moscow is the capital of France. Is that true or false?

Note: For the question, please be sure to use the rules of logic, not ordinary English!

{{#ev:youtubehd|4HWzU7RhfZE}}

The answers are first, the sentence if five is an odd number, then Paris is the capital of France, is true in propositional logic. It may sound odd in ordinary English, but in propositional logic, this is the same as true implies true and if we look on this line -- the final line for P and Q, P implies Q is true.a

The second sentence: five is an even number implies Moscow is the capital of France. That's the same as false implies false, and false implies false according to the definition is also true.

Question

{{#ev:youtubehd|ae_9TnTNPU0}}

Here's a quiz. Use truth tables or whatever other method you want to fill in the values of these tables. For each of the values of P and Q -- false/false, false/true, true/false, or true/true -- look at each of these boxes and click on just the boxes in which the formula for that column will be true. So for which of these four boxes, if any, will the formula be true? And this formula, and this formula.

I solved that with this javascript code:

function print( line ) { WScript.StdOut.WriteLine( line ); }

function implies( p, q ) {

if ( p === true && q === false ) { return false; }

return true;

}

function test( p, q ) {

var a = p && implies( p, q );

var b = ! ( ! p || ! q );

var c = a === b;

var line = p + "\t" + q + "\t" + a + "\t" + b + "\t" + c;

print( line );

}

print( "P\tQ\tA\tB\tC" );

test( false, false );

test( false, true );

test( true, false );

test( true, true );

{{#ev:youtubehd|vGfOrh8ERXo}}

Here are the answers. For P and P implies Q, we know that P is true in these bottom two cases, and P implies Q, we saw the truth table for P implies Q, is true in the first, second, and fourth case. So the only case that's true for both P and P implies Q is the forth case.

Now, this formula, not the quantity, not P or not Q, we can work that out to be the same as P and Q, we know that P and Q is true only when both are true, so that would be true only in the fourth case and none of the other cases.

And now, we're asking for an equivalent or biconditional between these two cases. Is this one the same as this one? And we see that it is the same because they match up in all four cases. They're false for each of the first three and true in the fourth one, so that means that this is going to be true no matter what. They're always equivalent, either both false or both true, and so we should check all four boxes.

Question

{{#ev:youtubehd|DDKhgqEWBps}}

Here's one more example of reasoning in propositional logic. In a particular model of the world, we know the following three sentences are true. E or B implies A. A implies J and M. And B.

We know those three sentences to be true, and that's all we know. Now, I want you to tell me for each of the five propositional symbols, is that symbol true or false or unknown in this model? And tell me for the symbols E, B, A, J and M.

{{#ev:youtubehd|pxGxSt58kg0}}

The answer is that B is true. And we know that because it was one of the three sentences that was given to us. And now, according to the first sentence, which says that if E or B is true then A is true. So now we know that A is true. And the second sentence says if A is true then J and M are true. What about E? That wasn't mentioned. Does that mean E is false? No. It means that it's unknown. That a model where E is true and a model where E is false would both satisfy these three sentences. So we mark E as unknown.

Terminology

{{#ev:youtubehd|nGZ2-EZnSh4}}

Now for a little more terminology. We say that a valid sentence is one that is true in every possible model, for every combination of values of the propositional symbols. And a satisfiable sentence is one that is true in some models, but not necessarily in all the models. So what I want you to do is tell me for each of these sentences, whether it is valid, satisfiable but not valid, or unsatisfiable, in other words, false for all models. And the sentences are:

I cheated and used the following code:

function print( line ) { WScript.StdOut.WriteLine( line ); }

function implies( p, q ) {

if ( p === true && q === false ) { return false; }

return true;

}

var p1 = [ [ false ], [ true ] ];

var p2 = [ [ false, false ], [ false, true ], [ true, false ], [ true, true ] ];

var p3 = [

[ false, false, false ],

[ false, false, true ],

[ false, true , false ],

[ false, true , true ],

[ true , false, false ],

[ true , false, true ],

[ true , true , false ],

[ true , true , true ]

];

function a( p ) { p = p[ 0 ]; return p || ! p; }

function b( p ) { p = p[ 0 ]; return p && ! p; }

function c( p ) { var q = p[ 1 ]; p = p[ 0 ]; return p || q || p === q; }

function d( p ) { var q = p[ 1 ]; p = p[ 0 ]; return implies( p, q ) || implies( q, p ); }

function e( p ) {

var food = p[ 0 ];

var party = p[ 1 ];

var drinks = p[ 2 ];

return implies( implies( food, party ) || implies( drinks, party ), implies( food && drinks, party ) );

}

function test( l, f, p ) {

var count = 0;

for ( var i in p ) {

if ( f( p[ i ] ) ) { count++; }

}

if ( count === 0 ) {

print( l + ": unsatisfiable" );

}

else if ( count === p.length ) {

print( l + ": valid (" + count + " out of " + p.length + ")" );

}

else {

print( l + ": satisfiable (" + count + " out of " + p.length + ")" );

}

}

test( "a", a, p1 );

test( "b", b, p1 );

test( "c", c, p2 );

test( "d", d, p2 );

test( "e", e, p3 );

{{#ev:youtubehd|WOYA5kQ_6gI}}

The answers are P and not P is valid. That is, it's true when P is true because of this, and it's true when P is false because of this clause.

P and not P is unsatisfiable. A symbol can't be both true and false at the same time.

P or Q or P is equivalent to Q is valid. So we know that it's true when either P or Q is true, so that's three out of the four cases. In the fourth case, both P and Q are false, and that means P is equivalent to Q. And therefore, in all four cases, it's true.

P implies Q or Q implies P, that's also valid. Now in ordinary English that wouldn't be valid. If the two clauses or the two symbols P and Q were irrelevant to each other we wouldn't say that either one of those was true. But in logic, one or the other must be true, according to the definitions of the truth tables.

And finally, this one's more complicated, if Food then Party or if Drinks then Party implies if Food and Drinks then Party. You can work it all out and both sides of the main implication work out to be equivalent to Not Food or Not Drinks or Party. So that's the same as saying P implies P, saying one side is equivalent to the other side. And if they're equivalent, then the implication relation holds.

Propositional Logic Limitations

{{#ev:youtubehd|WQ7-B4H6-aE}}

Propositional logic. It's a powerful language for what it does. And there are very efficient inference mechanisms for determining validity and satisfiability, although we haven't discussed them. But propositional logic has a few limitations. First, it can only handle true and false values. No capability to handle uncertainty like we did in probability theory. And second, we can only talk about events that are true or false in the world. We can't talk about objects that have properties, such as size, weight, colour, and so on. Nor can we talk about the relations between objects. And third, there are no shortcuts to succinctly talk about a lot of different things happening. Say if we had a vacuum world with a thousand locations, and we wanted to say that every location is free of dirt. We would need a conjunction of a thousand propositions. There's no way to have a single sentence saying that all the locations are clean all at once. So, we will next cover first-order logic which addresses these two limitations.

First Order Logic

{{#ev:youtubehd|hFzVZzMPy8Q}}

I'm going to talk about first order logic and its relation to the other logics we've seen so far -- namely, propositional logic and probability theory. And we're going to talk about them in terms of what they say about the world, which we call the ontological commitment of these logics, and what types of beliefs agents can have using these logics, which we call the epistemological commitments.

So in first order logic we have relations about things in the world, objects, and functions on those objects. And what we can believe about those relations is that they're true or false or unknown. So this is an extension of propositional logic in which all we had was facts about the world and we could believe that those facts were true or false or unknown.

Now in probability theory we had the same types of facts as in propositional logic -- the symbols, or variables -- but the beliefs could be a real number in the range 0 to 1. So logics vary both in what you can say about the world and what you can believe about what's been said about the world.

Another way to look at the representation is to break the world up into representations that are atomic, meaning that a representation of the state is just an individual state with no pieces inside of it. And that's what we used for search and problem solving. We had a state, like state A, and then we transitioned to another state, like state B, and all we could say about those states was are they identical to each other or not and maybe is one of them a goal state or not. But there wasn't any internal structure to those states.

Now, in propositional logic, as well as in probability theory, we break up the world into a set of facts that are true or false, so we call this a factored representation -- that is, the representation of an individual state of the world is factored into several variables -- the B and E and E and M and J, for example -- and those could be Boolean variables or in some types of representations -- not in propositional logic -- they can be other types of variables besides Boolean. Then the third type -- the most complex type of representation -- we call structured. And in a structured representation, an individual state is not just a set of values for variables,